INTERVIEW - 10 Years after the Paris Agreement, with Laurence Tubiana

In December 2024, C3A had the honor of hosting its First Annual Symposium in Paris, with an inspiring opening by Laurence Tubiana, a distinguished member of the C3A Scientific Committee. Laurence Tubiana kicked off the event by reflecting on the achievements and challenges of Paris+10, offering a thoughtful overview of the progress made over the past decade in global climate policy. Her insights set the tone for a series of discussions focused on advancing climate action and fostering collaboration across sectors.

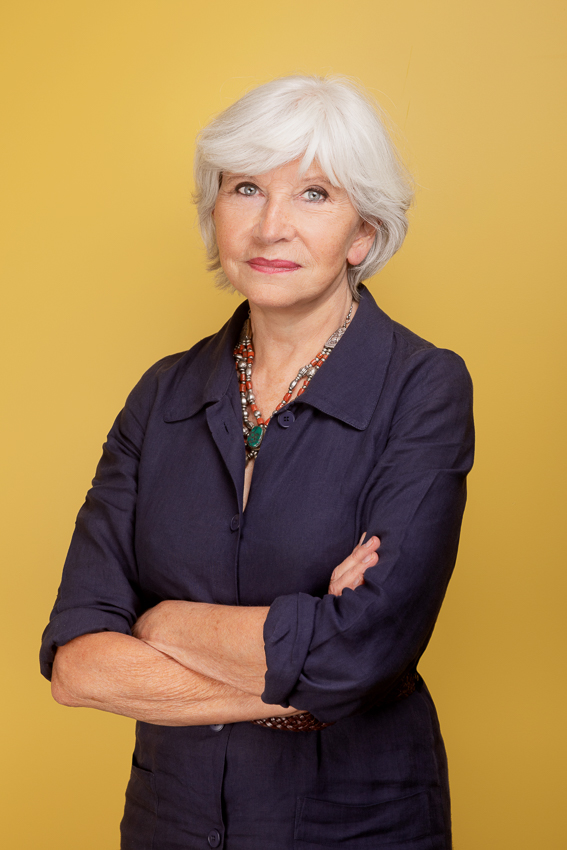

INTERVIEWEE

Laurence Tubiana is CEO of the European Climate Foundation (ECF) and a Professor at Sciences Po, Paris. She previously chaired the Board of Governors at the French Development Agency (AFD), as well as the Board at Expertise France (The French public agency for international technical assistance). Before joining the ECF, Laurence was France’s Climate Change Ambassador and Special Representative for COP21, and as such a key architect of the landmark Paris Agreement. Following COP21 and through COP22, she was appointed UN High-Level Champion for climate action.

Laurence Tubiana is CEO of the European Climate Foundation (ECF) and a Professor at Sciences Po, Paris. She previously chaired the Board of Governors at the French Development Agency (AFD), as well as the Board at Expertise France (The French public agency for international technical assistance). Before joining the ECF, Laurence was France’s Climate Change Ambassador and Special Representative for COP21, and as such a key architect of the landmark Paris Agreement. Following COP21 and through COP22, she was appointed UN High-Level Champion for climate action.

Laurence Tubiana brings decades of expertise. From 1997—2002, she served as Senior Adviser on the Environment to the French Prime Minister Lionel Jospin. From 2009—2010, she created and led the newly established Directorate for Global Public Goods at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. She founded in 2002 and directed until 2014 the Institute of Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI). She has held academic positions including Sciences Po and as Professor of International Affairs at Columbia University. She has been a member of numerous boards and scientific committees, including the Chinese Committee on the Environment and International Development (CCICED).

QUESTIONS

You played a crucial role in the Paris Agreement 10 years ago. How do you assess the progress made since then, and what are the main challenges that still hinder the implementation of the commitments made during COP21?

We should first of all acknowledge that we’ve made significant progress since 2015 and that the Paris Agreement has proven remarkably resilient. Global emissions should peak soon. Renewables are seeing exponential growth thanks to initiatives like the EU Green Deal and China’s mass production of low-carbon technologies. That’s supported by diplomatic efforts: in late 2023 the world finally agreed to move away from fossil fuels, the primary driver of emissions. But we undeniably need to move faster.

The biggest challenges we face are political and geopolitical. We’re seeing a co-ordinated effort by beneficiaries of the old economy to cling to outdated technologies. There are also undeniably difficult discussions about how richer countries should help poorer ones to transition and develop without being saddled with crushing levels of debt. We must return to the ‘spirit of Paris’, where countries surpass their narrow self-interest to tackle this problem which no country can solve alone.

By nature, international cooperation is an essential condition for fighting climate change. In your view, what are the key factors to strengthen this cooperation, and how can they be applied in a context of accelerated geopolitical fragmentation?

Geopolitics is clearly less conducive today, so we can't rely on the same driving forces as in 2015. But there are important new factors we need to consider that simply weren’t as relevant in 2015. Although climate change’s impacts have sadly worsened, the economics of climate change have seen the most dramatic change. There is now significant economic momentum for the transition thanks to ever-cheaper clean technologies. That has significantly shifted our perception of the costs and benefits of climate action.

Even so, the multilateral system must be protected and reinforced, not abandoned. Competition in green technologies is not a zero-sum game and multilateral co-operation is more essential than ever. No country – however powerful – can solve the crisis on its own, nor shield itself from the impacts of unmitigated climate change. I believe that climate action is one of the areas where there is still an appetite for joint solutions.

The last Climate COP revealed that financing climate action remains a major issue, especially for the most vulnerable countries. In your opinion, what are the most promising solutions to increase investment in the low-carbon transition? What are the priorities that need to be addressed to ensure more effective and sustainable support in the coming years?

The Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance has said that achieving the Baku to Belem Roadmap to $1.3T means leveraging a toolbox of financial sources. That includes grants, concessional finance, guarantees, and innovative solutions like solidarity levies to bridge the financing gaps. Priorities include translating NDCs into investment/transition plans and incentivizing private sector participation.

Promising work is well underway. For example, the German government has asked the European Climate Foundation and GIZ to co-lead the secretariat for its Green Guarantees Group (GGG). Designed as a marketplace of ideas, the GGG aims to unlock private finance for EMDEs. It will produce solutions-oriented recommendations for decision-makers and a path forward to significantly increase green guarantees’ use. It will serve as a forum to better understand and overcome limits of guarantees in order to improve risk management and build on existing initiatives such as the World Bank’s Guarantee Platform hosted at MIGA.

What role could a solidarity-based taxation mechanism play in such a financing framework for the low-carbon transition? Could you tell us more about your agenda on this point?

Solidarity levies have enormous potential to become a new source of climate and development finance. Many polluting sectors of our economy are undertaxed and not paying for the problem they have caused. It is only fair that we look at how we tap into this - it could raise hundreds of billions in concessional finance. There is significant momentum behind this idea.

In 2023, Barbados, France and Kenya launched the Global Solidarity Levies Task Force. I was honoured to have been asked to lead its Secretariat alongside former top South African Treasury official Ismail Momoniat. Its 17 member governments are working to bring together at COP30 a coalition of the willing ready to implement one or several levies whose proceeds will be used for climate and development. There is particular

enthusiasm around the potential of a levy on aviation tickets, or a levy on fossil fuel extraction, as well as a financial transactions tax.

In December 2024, during the First C3A Symposium in Paris, you opened the first chapter of an international conference held over a week, bringing together countries and scientists from five continents to discuss the role of Ministries of Finance during the potentially uncertain and turbulent phase of the transition. In light of this Symposium, do you have a message for the Ministries of Finance and the climate policy scientists and experts working with them regarding the priorities for action and knowledge to focus their efforts on, particularly in preparation for COP30 in Brazil?

Finance Ministries are of course custodians of the public purse and rightly exert fiscal prudence to responsibly steward public funds. My message to finance ministries is a question: one of timelines. How to balance the short-term cost with the long-term gain (or avoidance of loss)?

In a time of increasing climate damages and transition costs, consider the trade-offs you inevitably make between short-term fiscal consolidation and long-term stability. Keeping public debt and inflation in check in the long term requires us to address structurally destabilizing forces in the short and medium terms. It’s of course up to you to balance those risks as you see fit, but you must not forget that short-term savings can create long-term costs which are orders of magnitude greater.

We need innovative fiscal policy to rise to the day’s challenges and create long-term stability, albeit at a short-term cost. There is always a way forward.